| Expert Summary

The Trial Balance is an internal accounting report verifying the arithmetic accuracy of the General Ledger by ensuring Total Debits equal Total Credits. It is the essential prerequisite for preparing reliable financial statements (Income Statement and Balance Sheet). |

The foundation of a reliable financial reporting system lies in a core principle: every debit must have a corresponding credit. This is the bedrock of the double-entry accounting system, and the Trial Balance serves as the initial, crucial test of this principle’s integrity.

A Trial Balance is a detailed report that consolidates the closing balance of every account in a company’s general ledger at a specific point in time. It is an internal document, typically prepared at the end of an accounting period, that systematically lists all account balances, assets, liabilities, equity, revenues, and expenses,separated into a debit column and a credit column.

For accounting students, small business owners managing their own books, and junior accountants, the Trial Balance is more than just a list of numbers; it is a vital checkpoint. Its primary purpose is to prove the mathematical accuracy of the ledger. If the total of the debit column exactly equals the total of the credit column, the books are considered balanced. A balanced Trial Balance indicates that all transactions have been correctly posted in accordance with the double-entry method, providing the necessary assurance before moving on to the preparation of formal financial statements. This guide will clarify the format, types, and practical significance of this indispensable accounting tool.

The Critical Checkpoint: Ensuring Integrity in Financial Reporting

The integrity of a business, from the perspective of an investor, creditor, or manager, is fundamentally tied to the accuracy and reliability of its financial reports. Preparing a Balance Sheet and Income Statement the documents that communicate a company’s financial health and performance requires absolute confidence in the underlying accounting data. Any error introduced early in the process will compromise these final, public-facing statements. This is where the Trial Balance serves its indispensable role.

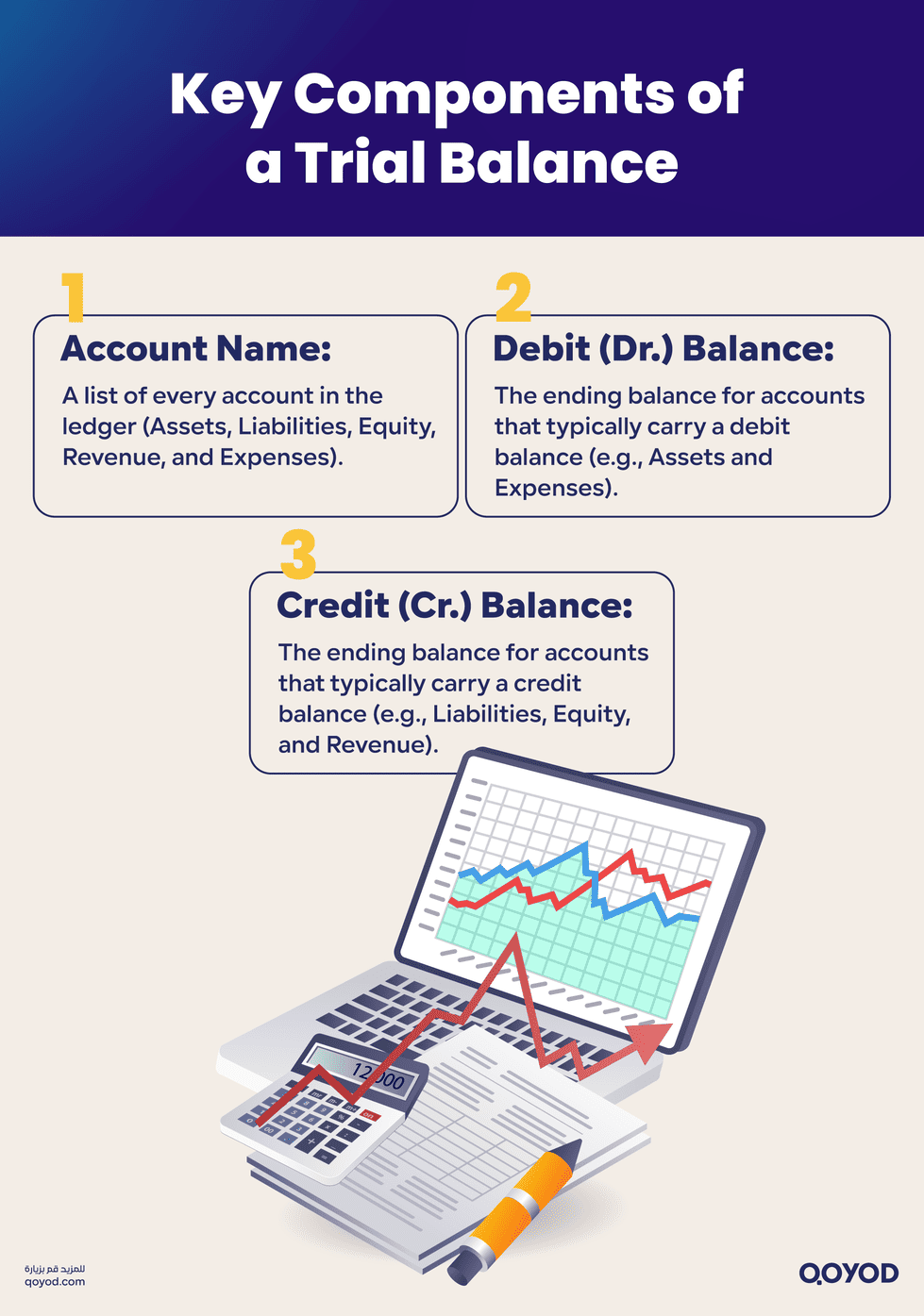

What is a Trial Balance?

A Trial Balance is an internal report that extracts the closing balance of every account in a company’s General Ledger at a specific point in time (e.g., month-end or year-end). It is presented in a simple, columnar format with two main sections:

- Account Name: A list of every account in the ledger (Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, and Expenses).

- Debit (Dr.) Balance: The ending balance for accounts that typically carry a debit balance (e.g., Assets and Expenses).

- Credit (Cr.) Balance: The ending balance for accounts that typically carry a credit balance (e.g., Liabilities, Equity, and Revenue).

Read Also: What are assets? And what are their types?

The single, most crucial objective of this report is to verify the core mathematical principle of the double-entry accounting system:

Total Debits = Total Credits

By preparing the Trial Balance, accountants test whether the total sum of all debit balances exactly equals the total sum of all credit balances. If the totals match, the books are considered arithmetically balanced, providing a strong indication that all journal entries were correctly posted to the general ledger.

A Crucial Step in the Accounting Cycle

The Trial Balance is an essential checkpoint that links the detailed day-to-day transaction records (journals and ledgers) to the summary financial statements. It is performed before the preparation of the formal Income Statement and Balance Sheet.

- If the Trial Balance does not balance (Total Debits ≠ Total Credits), it signals an immediate error in the recording or posting process that must be located and corrected before proceeding.

- If the Trial Balance does balance, it provides the necessary foundation of verified, summarized data to construct the final reports that stakeholders rely on for informed decision-making. Without this crucial verification step, the resulting financial statements would be unreliable.

Trial Balance vs. Financial Statement

It is essential to understand what a Trial Balance is not.

The Trial Balance is NOT a Financial Statement.

It is an internal working paper or report a bookkeeping tool used by the accountant. Unlike the Balance Sheet and Income Statement, it is not formally presented to external parties (like investors or banks) as a summary of financial performance or position. Its sole purpose is verification; it serves as the crucial source document from which the formal, external financial statements will be prepared.

The ability of a Trial Balance to prove Total Dr. = Total Cr. confirms that the accounting records are arithmetically sound, clearing the way for the next stage in the accounting cycle.

Why is a Trial Balance Important? (Key Objectives)

The significance of the Trial Balance extends far beyond simply creating a list of account balances. It is a critical risk mitigation tool that directly supports the reliability of all financial data. For accounting students, business owners, and junior accountants, understanding its core objectives is crucial for grasping the logic of the entire accounting cycle.

Essential Roles and Key Objectives

The Trial Balance serves three primary, high-value functions:

- Accuracy Check (Verifying Arithmetic Integrity)

Its fundamental purpose is to perform a systematic verification of the General Ledger. It proves that the recording and posting process adhered strictly to the double-entry rule.

By confirming that Total Debits equal Total Credits, the Trial Balance verifies the arithmetical accuracy of the bookkeeping process up to that point. If the ledger is unbalanced, the Trial Balance immediately flags this by failing to equate the two columns. - Error Detection (Locating Posting Errors)

While a balanced Trial Balance doesn’t guarantee the records are perfect, a non-balancing one signals an immediate, quantifiable problem. It is the first step in the error detection and correction process. The difference between the Debit and Credit totals often provides a clue to the nature of the error:

Transposition Error: If the difference is divisible by 9, a common error is transposing digits (e.g., writing 520 SAR instead of 250 SAR).

Single Entry Error: If the difference equals a known transaction amount, it suggests a transaction was only recorded as a debit or a credit, but not both. This report helps narrow the search for errors, preventing more severe complications later.

- Basis for Financial Statements (Source Data)

The final, verified Trial Balance provides the summarized, correct raw data required to construct the external financial reports. It organizes the entire General Ledger into a single, usable document:

Income Statement (Profit & Loss): Revenue and Expense accounts are extracted from the Trial Balance.

Balance Sheet (Statement of Financial Position): Asset, Liability, and Equity accounts are extracted from the Trial Balance.

In essence, the Trial Balance transforms thousands of individual transactions into a manageable summary, acting as the certified source document from which a company’s financial story is told.

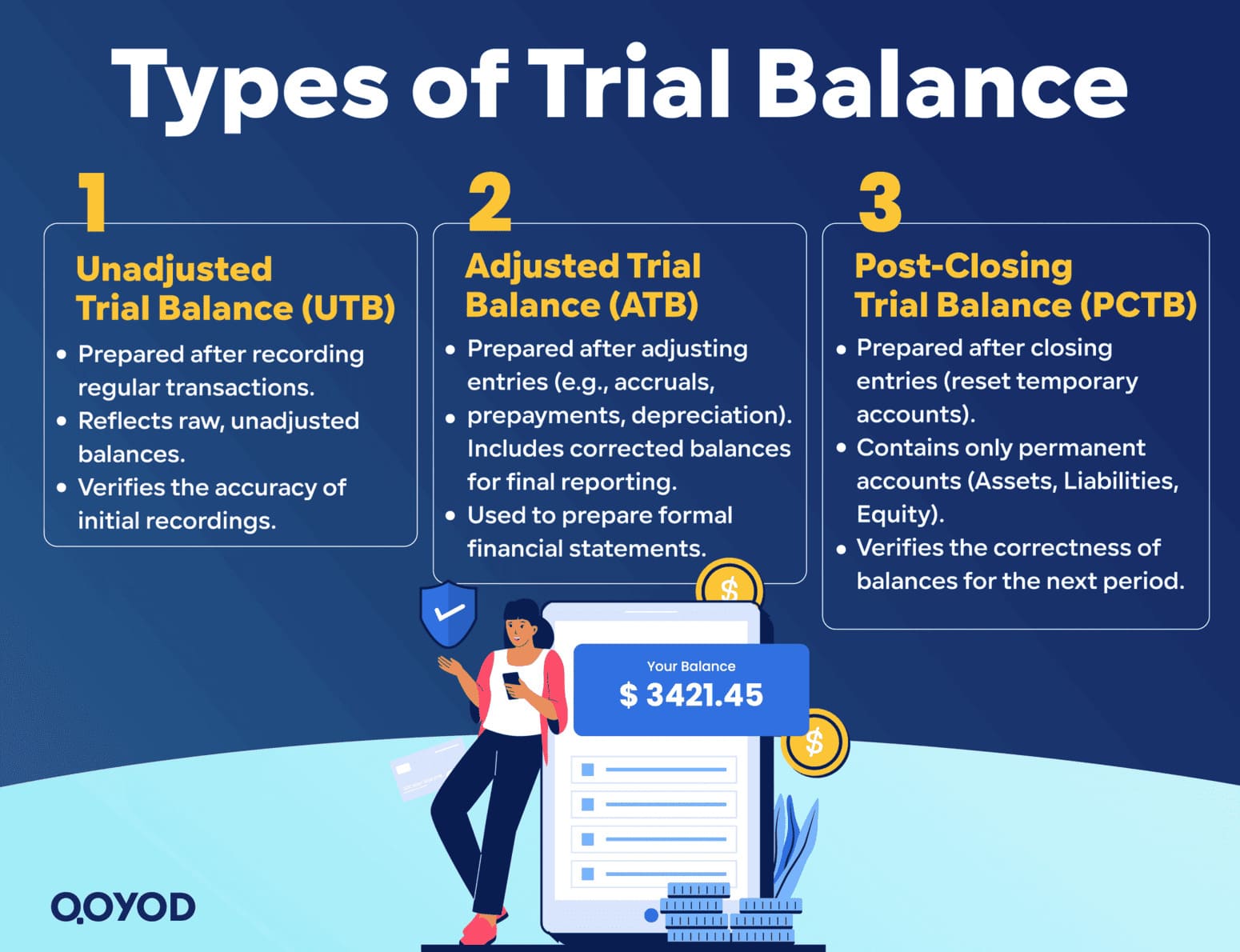

Types of Trial Balance

While the core function of testing the equality of debits and credits remains constant, the Trial Balance is prepared at various distinct stages throughout the accounting cycle, resulting in three primary types. Each serves a specific purpose in verifying the books before moving to the next phase of financial reporting.

Unadjusted Trial Balance (UTB)

The Unadjusted Trial Balance (UTB) is the first version prepared. It is created immediately after all regular day-to-day transactions (e.g., sales, purchases, payments) have been recorded in the journals and subsequently posted to the General Ledger.

The UTB reflects the raw, summarized balances of all accounts before any internal adjustments are made. Its purpose is to verify the arithmetic accuracy of the initial recording process and provide the foundation data for the adjustment phase.

Adjusted Trial Balance (ATB)

The Adjusted Trial Balance (ATB) is the second, and most critical, version. It is prepared after the accountant has recorded and posted all adjusting entries to the General Ledger.

Adjusting entries are non-cash transactions made at the end of the period to ensure revenues and expenses are recognized in the correct period (following the accrual basis of accounting). These include entries for:

- Accruals (unrecorded revenues and expenses).

- Prepayments (allocating prepaid assets like insurance over time).

- Depreciation (recording the use of long-term assets).

The ATB contains the final, correct balances of all accounts (including the adjusted balances) required to prepare the formal Income Statement and Balance Sheet.

Post-Closing Trial Balance (PCTB)

The Post-Closing Trial Balance (PCTB) is the final Trial Balance prepared at the very end of the accounting cycle. It is generated after the closing entries have been made.

Closing entries are journal entries used to reset the balances of all temporary accounts (Revenues, Expenses, and Drawings/Dividends) to zero, transferring their net effect (net income or loss) into a permanent equity account (Retained Earnings or Owner’s Capital).

The PCTB contains only permanent accounts (Assets, Liabilities, and Equity). It serves as the final verification check, ensuring that the temporary accounts have been correctly closed and that the permanent accounts have the correct opening balances for the start of the next accounting period.

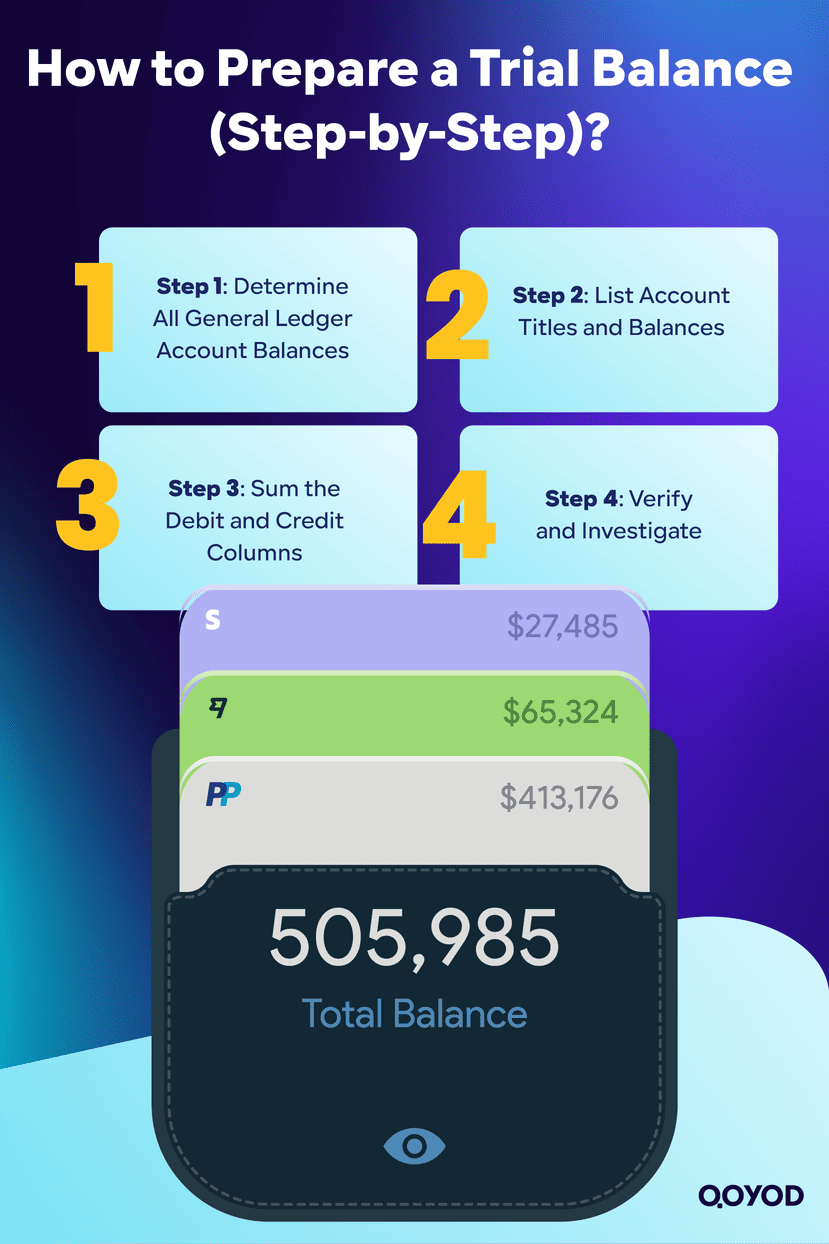

How to Prepare a Trial Balance (Step-by-Step)

The preparation of a Trial Balance is a straightforward, mechanical process that follows the completion of all standard journal entries and postings for the accounting period. It transforms the scattered data in the General Ledger into a consolidated, verifiable report.

Here is the step-by-step process for preparing the Unadjusted Trial Balance:

Step 1: Determine All General Ledger Account Balances

The first action is to close or total all accounts in the General Ledger to find the final ending balance for each one.

- For every T-account (ledger account), sum the totals of the debit side and the credit side.

- Subtract the smaller sum from the larger sum to find the closing balance.

- The balance is designated as Debit or Credit based on the side with the larger total. For example, if the debit side of the Cash account is larger than the credit side, the Cash account has a debit balance.

Step 2: List Account Titles and Balances

Create the three-column format (Account Title, Debit, Credit) and systematically list all accounts from the General Ledger, in the following standard order:

- Assets

- Liabilities

- Equity (Capital and Drawings)

- Revenues

- Expenses

Ensure each account balance is placed in its corresponding normal balance column:

- Assets and Expenses go into the Debit column.

- Liabilities, Revenue, and Equity go into the Credit column.

Step 3: Sum the Debit and Credit Columns

Once all account balances have been recorded in the correct column, calculate the final total for each column separately.

- Add up all the figures in the Debit column.

- Add up all the figures in the Credit column.

Step 4: Verify and Investigate

The final and most crucial step is the verification check:

- Verification: Compare the total of the Debit column to the total of the Credit column.

- Success: If Total Debits = Total Credits, the Trial Balance is balanced, and the General Ledger is arithmetically accurate. The accountant can proceed to make adjusting entries.

- Failure: If Total Debits ≠ Total Credits, an error exists in the journals or the posting process. The accountant must stop and investigate the difference to locate and correct the error before proceeding.

Trial Balance Format (With Example)

To provide a clear, practical understanding for accounting students and small business owners, here is the standard format of a completed Trial Balance. This example demonstrates how the balances from all permanent and temporary accounts are organized to prove the equality of debits and credits.

Final Corrected Illustrative Example

We ensure the total debits exactly equal the total credits, fulfilling the primary requirement of a Trial Balance.

Sample Company

Unadjusted Trial Balance

As of December 31, 2024

| Account Title | Account Type | Debit (SAR) | Credit (SAR) |

| 101 Cash | Asset | 18,500 | |

| 112 Accounts Receivable | Asset | 4,000 | |

| 157 Equipment | Asset | 15,000 | |

| 201 Accounts Payable | Liability | 3,000 | |

| 301 Owner’s Capital | Equity | 25,000 | |

| 306 Owner’s Drawings | Equity (Contra) | 1,500 | |

| 401 Service Revenue | Revenue | 14,000 | |

| 610 Rent Expense | Expense | 2,000 | |

| 631 Utilities Expense | Expense | 1,000 | |

| TOTALS | 42,000 | 42,000 |

Verification: The totals for the Debit column (42,000 SAR) and the Credit column (42,000 SAR) now match. This confirms that the Trial Balance is arithmetically balanced, a necessary step before preparing financial statements. Although this balance ensures mathematical accuracy, it does not guarantee the absence of all accounting errors, such as omitted transactions or incorrect account postings.

Common Errors Not Revealed by the Trial Balance

A balanced Trial Balance provides vital assurance of arithmetical accuracy, confirming that the total debit entries equal the total credit entries. However, for both students and professional accountants, it is crucial to recognize a fundamental limitation: A balanced Trial Balance does not guarantee the financial records are free of errors.

The Trial Balance is incapable of detecting errors that impact both the debit and credit sides equally, thus maintaining the Total Debits = Total Credits. These errors must be caught through internal controls, reconciliations, and review processes.

Here are the most common types of errors that a Trial Balance will not reveal:

- Error of Omission

This occurs when an entire transaction is completely missed (omitted) from the books. Since the journal entry was never recorded, the double-entry rule was not violated neither a debit nor a credit was ever posted.

Example: A company pays an outstanding invoice of SAR 500 but forgets to record the transaction (Debit to Accounts Payable, Credit to Cash). Since both the debit and credit sides are equally understated by SAR 500, the Trial Balance remains in balance, but the financial statements are incorrect. - Error of Commission

This error involves correctly recording the dual-entry aspect of a transaction but posting one or both parts to the wrong account, provided the incorrect account has the same normal balance (Debit or Credit) as the correct one.

Example: A payment for Rent Expense (a debit) of SAR 1,000 is mistakenly debited to the Utilities Expense account (also a debit). The total debit column remains correct (SAR 1,000), and the Trial Balance balances, but the individual expense accounts are misrepresented. - Compensating Errors

This is the most deceptive type, where two or more unrelated errors cancel each other out, leading to a balanced Trial Balance by coincidence.

Example: An account payable transaction is incorrectly under-credited by SAR 200 (Error 1). Simultaneously, a cash receipt transaction is incorrectly under-debited by SAR 200 (Error 2). The total of the Credit column is artificially lower by SAR 200, but the total of the Debit column is also lower by SAR 200. The errors compensate, the Trial Balance balances, but the individual account figures are wrong. - Error of Original Entry

If the amount entered in the original journal entry is incorrect, and that incorrect amount is then posted as an equal debit and credit to the ledger, the Trial Balance will balance.

Example: A SAR 9,000 payment is mistakenly recorded in the journal as SAR 900. The ledger accounts are debited and credited by SAR 900. Since the debits equal the credits, the Trial Balance balances, but the true value of the transaction is missed by SAR 8,100.

These limitations underscore why the Trial Balance is merely a preliminary check. Accountants must perform additional procedures, such as bank reconciliations and subsidiary ledger confirmations, to ensure true financial statement accuracy.

Trial Balance vs. Balance Sheet

The terms Trial Balance and Balance Sheet are often confused, particularly by beginners, due to their similar-sounding names and reliance on debit and credit balances. However, they serve fundamentally different purposes within the accounting and reporting process. The Trial Balance is an internal tool for verification, while the Balance Sheet is an external report for communication.

Here is a clear distinction between the two documents:

| Feature | Trial Balance (TB) | Balance Sheet (BS) |

| Primary Purpose | To test the arithmetic accuracy of the general ledger (ensure Total Debits = Total Credits). | To report the company’s financial position at a specific date. |

| Output Goal | Verification: Sum of Debits = Sum of Credits | Presentation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity). |

| Content | Lists ALL account balances (Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, and Expenses). | Lists ONLY permanent accounts (Assets, Liabilities, and Equity). |

| Reporting Status | Internal working document. Never formally issued to external stakeholders. | External financial statement. Issued to investors, creditors, and regulators. |

| Time in Cycle | Prepared before the creation of the Income Statement and Balance Sheet. | Prepared after the Trial Balance and adjusting entries are completed. |

The Trial Balance is the essential raw data summary from which the Balance Sheet (and Income Statement) is compiled. The mathematical equality found in the TB is necessary to construct the equality found in the BS:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Trial Balance: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

To address common queries from small business owners and accounting students, here are brief answers to key questions about the Trial Balance:

Does a trial balance detect all accounting errors?

No, a Trial Balance does not detect all errors. It is designed only to check the equality of total debits and total credits. It will fail to detect errors that affect both columns equally, such as an Error of Omission (missing an entire transaction), posting to the wrong correct-side account (Error of Commission), or Compensating Errors where two mistakes cancel each other out.

Is the trial balance a financial statement?

No. The Trial Balance is an internal accounting schedule or working paper. It is a preliminary report used by accountants to verify the arithmetic accuracy of the General Ledger before preparing the formal, external financial statements, such as the Income Statement and the Balance Sheet.

What happens if the trial balance doesn’t match?

If the totals do not match, the accountant must immediately investigate the ledger and journals to find the error. Common practice is to re-check postings and calculations. If the period-end deadline is imminent, the difference may temporarily be placed into a Suspense Account to allow the financial statements to be drafted, but this account must be cleared (zeroed out) as soon as the source of the discrepancy is found.

Conclusion: The Bridge to Reliable Reporting

The Trial Balance stands as the definitive, internal cornerstone of the double-entry accounting system. It is the critical bridge that connects the thousands of individual, day-to-day transactions recorded in the journals and ledgers with the summarized, formal documents required for external communication.

By demanding the strict equality between total debits and total credits Total Debits = Total Credits, the Trial Balance serves as the primary verification tool for all accounting students, small business owners, and junior accountants. It confirms the arithmetic soundness of the records before adjustments are made, ensuring that the resulting Income Statement and Balance Sheet are built upon reliable data.

While a balanced Trial Balance is a significant achievement, users must always remember its limitations; it proves mathematical balance, not the absolute accuracy of the underlying classifications.

In the modern business environment, manual preparation is increasingly rare. Accounting software (like QuickBooks, SAP, or Xero) automatically generates the Unadjusted and Adjusted Trial Balances instantly as transactions are entered. Understanding the concept, format, and purpose of the Trial Balance remains essential, however, as it empowers users to interpret the software’s output, locate discrepancies quickly, and maintain the true integrity of the financial records. Mastering the Trial Balance is, therefore, a fundamental prerequisite for moving forward in the accounting cycle and ensuring credible financial reporting.